The world has a special fascination with Ancient Egypt that has been going strong since the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen and his spectacularly bling funerary mask. After being unearthed by a rather controversial expedition in 1922 by the British, which ended up with quite a few of its members dead shortly after and spawning rumors of ancient magic and curses, this celebrity mummy ignited a passion for the Pharaohs that turned Egypt into a prime destination for researchers and tourists alike.

Today, we have quite a reasonable understanding of what the ancient Egyptians were all about. We have learned about their belief systems, their innumerable gods and their relations to almost every event that could happen in life, their complex use of agriculture in relation to the flow of the Nile, the elaborate burial traditions in which they took part, or their governmental hierarchy with the almighty Pharaohs always at the top of the (no pun intended) pyramid.

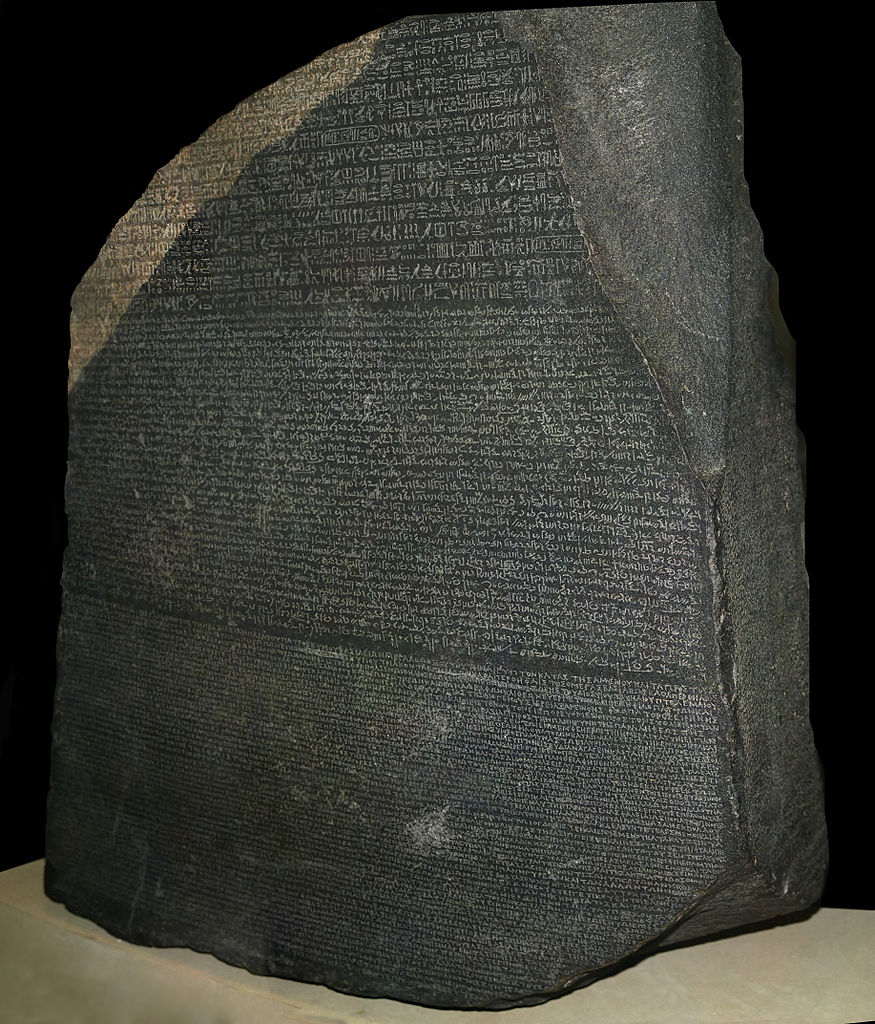

But there was a time when all of this was shrouded in almost complete mystery. There had been multiple attempts to decipher the hieroglyphs that the Egyptians used as their language, all of them resulting in very little progress at best, and complete failure at worst. The few references that existed to aid this task, such as the writings purportedly explaining 200 glyphs by the 5th Century priest Horapollo, were later found to be largely misleading and added further confusion to the whole endeavor.

However, this enduring veil of mystery that had lasted centuries was lifted by one single chance discovery in 1799 during the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt, by a mathematician turned soldier named Pierre-François Bouchard. While undertaking fortification tasks near the port city of Rosetta (modern day Rashid) in order to aid the war effort, he discovered a large granodiorite fragment filled with carvings which he immediately recognized as important and reported the find to his superiors who proceeded to secure it.

But war zones aren’t the best places for historical artifacts, and the French army eventually lost the fortification and had to retreat to Alexandria. The stone was held there for as long as the French defended the city, but finally the British forces gained the upper hand and conquered Alexandria and everything within, including the stone. After a few difficulties surrounding the handing over of artifacts, including threats from the French to burn all of them if necessary, an agreement was eventually reached and the stone was shipped back to Britain for further study, landing in Portsmouth in February 1802.

Now in the hands of scholars, the meaning of previously undecipherable Egyptian hieroglyphs of old was finally revealed. The stone itself contained fragments of the same text in three different languages: Greek, Demotic (a late Egyptian script that was still partially understood), and most important of all, Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic text.

The meaning of the actual text isn’t particularly interesting or revealing. In fact, it’s rather underwhelming in comparison to the monumental discovery from which it is part of. The writing describes a decree that was passed to affirm the royal status of King Ptolemy V, and then proceeds to list a series of good deeds he had done for the temples and priests of the land, in which has become possibly the first recorded instance of ancient political propaganda. Some things never change after all.

Regardless of the unimportance of the message, the fact is that one single translation managed to unlock a series of enigmas that were so elusive, they had historians scratching their heads for the better part of two millennia. A single translation transformed a collection of landmarks, artifacts, and incomprehensible carvings into a rich and deep culture that was far ahead of its time, and that we still love to research and discover well into the 21st Century and beyond.

Image resource: Tutankamón